Highlights:

- For many social programs, it is important from a policy perspective to know not just whether the program produces positive effects in the short term, but whether the effects endure long enough to constitute a meaningful improvement in participants’ lives.

- Unfortunately, we know from the history of rigorous evaluations that short-term program effects often fade over time.

- In this report, we provide graphical examples of fade-out that span different areas of social policy—workforce development, opioid addiction treatment, and postsecondary education—along with two exceptional examples of effects that endure over time.

- The bottom line is that, for many programs, relying on short-term positive findings as evidence of program effectiveness is hazardous, as the true impact may be fleeting and the ultimate effect on participants’ lives marginal. Doing so can also blind researchers and policy officials to the need for program enhancements or changes that might lead to a more enduring effect, or to the need for development and testing of new programs.

For many social programs, it is important from a policy perspective to know not just whether the program produces positive effects in the short term, but whether the effects endure long enough to constitute a meaningful improvement in participants’ lives. In the case of a youth drug abuse prevention program, for instance, the hope is that the program will produce a sustained reduction in drug use over time. If a high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) finds an effect on drug use six months after the study’s inception but no effect at the one-year mark or thereafter, it would be a disappointing result. The same would be true of an RCT in education that finds a positive effect on students’ reading achievement at the end of the school year but no effect on their reading scores or other educational outcomes in any subsequent year, or an RCT of intensive job training that finds a positive short-term effect on employment and earnings that dissipates within a year or two of program completion.

Unfortunately, we know from the history of rigorous evaluations that short-term program effects often fade. Below we provide graphical examples of fade-out that span different areas of social policy, along with two exceptional examples of effects that endure over time. Our key point is that, for many programs, relying on short-term positive findings as evidence of program effectiveness is hazardous, as the true impact may be fleeting and the ultimate effect on participants’ lives marginal. Doing so can also blind researchers and policy officials to the need for further program development—such as booster sessions, or other revisions or enhancements—that might lead to a more enduring effect, or to the need for the development and testing of new programs.

The graphical examples, based on well-conducted RCTs, are shown below. These examples focus on programs for which success from a policy standpoint would be a sustained, not just short-term, improvement in participants’ lives (we recognize that other types of social programs with other aims exist[i]).

1. The Enhanced Transitional Jobs Demonstration for ex-offenders and non-custodial, low-income parents

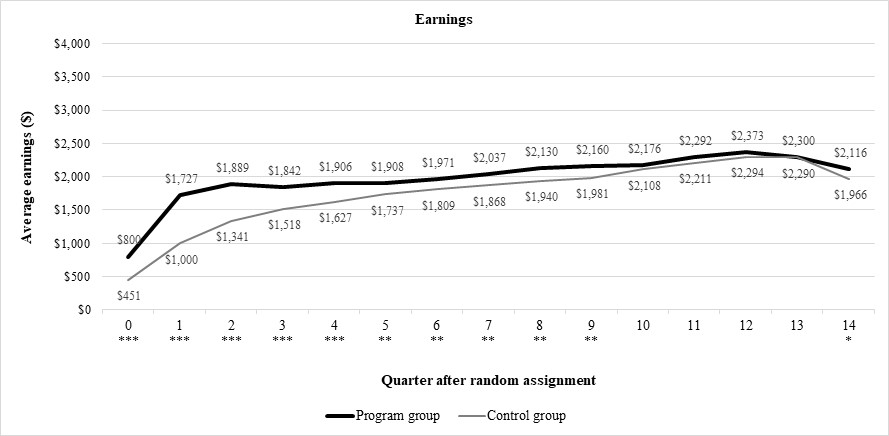

This was a large, federally-sponsored RCT, conducted by MDRC, that evaluated seven different “enhanced” transitional jobs programs for either (i) recently-released prisoners (three sites) or (ii) non-custodial, low-income parents who owed child support (four sites). The programs provided participants with short-term, subsidized jobs, as well as additional services that were aimed at fostering sustained workforce success and varied across the seven sites (e.g., peer mentoring, assistance in transitioning to a non-subsidized job). The programs’ cost to the government ranged from about $7,000 to $11,000 per person across the sites. The following graph shows the program effects on earnings for the pooled sample of 6,997 individuals over the 14 quarters (3.5 years) after random assignment:

***p<0.01 **p<0.05 *p<0.10

As you can see, the program group had much higher earnings than the control group in the early part of the follow-up period, amounting to several hundred dollars per quarter. The effects remain, but are smaller, after the subsidized jobs (and the earnings they generate) end in quarters 5-6. However, by quarter 10 the earnings effects have faded to near zero and remain there for the duration of the follow-up period. The study found a similar fade-out of effects on participants’ employment rate over the follow-up period. (As a side note: While the pooled earnings effects across the seven sites were disappointing, one site—San Francisco—showed meaningful sustained effects that we believe may warrant further study including potentially a replication trial.) Source: MDRC 2018.

2. Extended-Release Naltrexone—a medication to treat opioid addiction

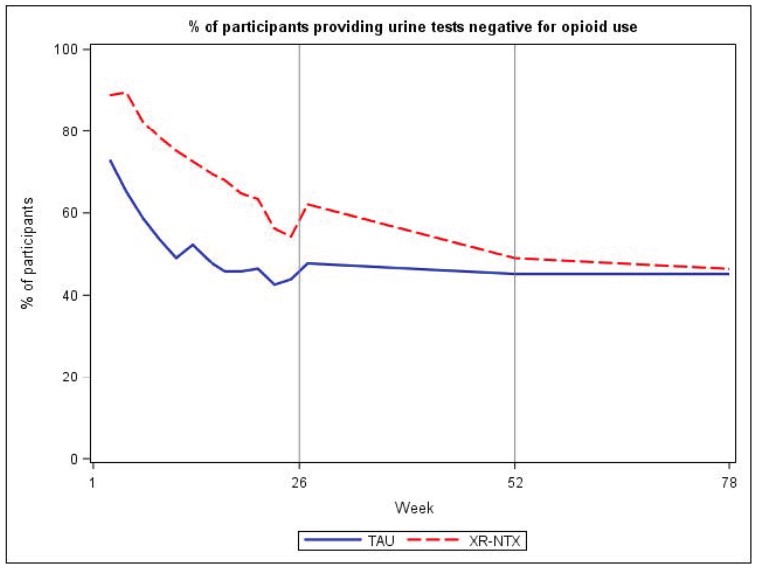

This RCT evaluated the effect of offering previously-incarcerated adults with a history of opioid dependence a 24-week course treatment of extended release naltrexone—an FDA-approved injectable medication for the prevention of opioid relapse. The sample comprised 308 adult volunteers who were abstinent from opioids at study entry. The following graph shows the treatment’s effect on opioid use from the period shortly after program entry through 78 weeks (1.5 years) post-entry:

As you can see, the treatment group (red line) has a much higher rate of negative urine tests—indicating abstinence from opioid use—than the control group (blue line) over the 24-week course of treatment, but the effect fades rapidly after treatment completion. By 78 weeks (1.5 years) after program entry, the effect had dissipated completely, as 46 percent of both groups—treatment and control—tested negative for opioids (i.e., 54 percent of both groups were using opioids again). Thus, hopes that the treatment would produce a lasting reduction in opioid dependence were not realized, signaling the need for development and testing of alternative protocols (e.g., a longer course of naltrexone) or alternative treatments. Source: Lee et. al., 2016.

This study is a rare example of a high-quality RCT of medication for opioid addiction that measures opioid use over a reasonably long period of time. The latest evidence reviews of such medications by the widely-respected Cochrane Collaboration (Buprenorphine maintenance, Methadone maintenance, Maintenance treatments for opiate-dependent adolescents, and Opioid agonist treatment for pharmaceutical opioid dependence) show a sizable number of RCTs but, with the exception of two small studies conducted more than 35 years ago, the RCTs all measure opioid use outcomes over only a short period of time (one year or less, and typically about 12 weeks).[ii]

Most of the medications included in these reviews are ongoing (“maintenance”) treatments for opioid addiction, and it is possible they have a more enduring effect than the time-limited (24-week) course of naltrexone. But until more long-term RCTs of such medications are conducted, we won’t know whether this is true or whether fade-out applies to these treatments as well.

3. Summer counseling after high school for college-intending, low-income high school graduates

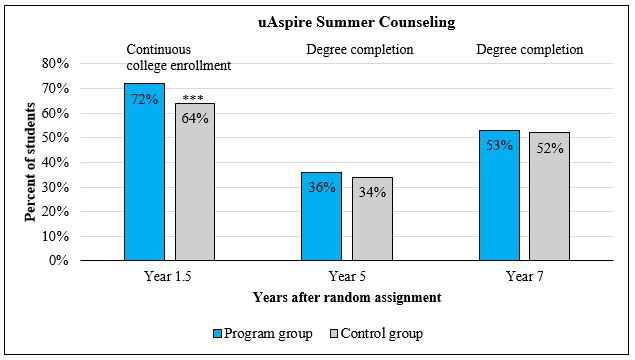

This was an RCT of a program, delivered by the uAspire organization, in which counselors met with college-intending, low-income students during the summer before college and advised them on steps needed to enroll successfully in the fall (e.g., addressing unmet financial need, meeting summer deadlines at the college they planned to attend). This was a sizable study, with a sample of 927 students. The following graph shows the program’s effects on college enrollment and completion over the seven-year period following random assignment:

***p<0.01

***p<0.01

As you can see, the initial program effects—including an eight percentage point increase in continuous college enrollment through fall of sophomore year—were promising. Unfortunately, the early effects on enrollment did not lead to the hoped-for longer-term effects on college completion. By the seventh year after random assignment, an almost identical percentage of program and control group members had completed a college degree.[iii] The researchers found a similar fade-out effect in two other RCTs they conducted to evaluate the effect of personalized summer text-message reminders to high school seniors about the steps needed to successfully enroll in college. Sources: Castleman, Page, and Schooley 2014, Castleman and Page 2018. [Disclosure: the Laura and John Arnold Foundation funded long-term follow-up in the summer counseling and text-message studies.]

4. The good news is that some program effects do endure: Two examples

Postsecondary Education—City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (CUNY-ASAP)

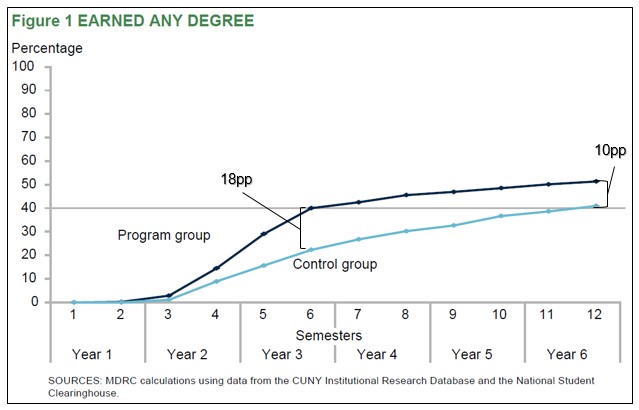

CUNY-ASAP is a comprehensive community college program that provides academic, personal, and financial supports to low-income students who need remedial education, with the goal of increasing college graduation rates. The program was evaluated in an RCT with a sample of 896 students. The following graph shows the program’s effects on college degree completion over the six-year period following random assignment:

As you can see, the effect on degree completion peaked in year three when the program group’s rate of degree completion was 18 percentage points higher than that of the control group. The difference narrowed by year six but remained substantial (10 percentage points, and statistically significant at the 0.01 level). Further narrowing in the future is unlikely as few sample members were still enrolled in college in year six. Source: MDRC 2017.

K-12 Education—Career Academies in high-poverty high schools

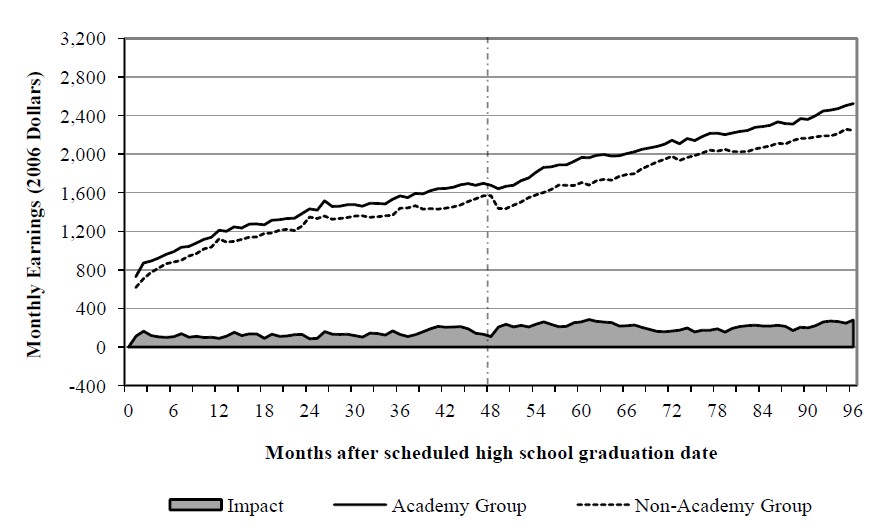

Career Academies are small learning communities in low-income high schools that combine academic and technical/career curricula, and offer workplace opportunities through partnerships with local employers. Career Academies were evaluated in a multisite RCT with a sample of 1,764 eighth and ninth grade students. The following graph shows the program’s effects on earnings over the eight years (96 months) following scheduled high school graduation:

Earnings Over the Eight Years Following Scheduled High School Graduation

As you can see, the earning effects endure over the full follow-up period with no sign of fading. In the final year of follow-up (i.e., year eight), the Academy group’s average earnings were 11 percent higher—$3,520 in 2019 dollars—than earnings of the control group. This effect was statistically significant (p=0.02). In addition, the cumulative earnings gains over the eight years ($21,300 per person) far exceeded the program’s modest cost.[iv] Source: MDRC 2008.

Concluding observations:

Some readers may wonder what causes fade-out of program effects. A full discussion of possible causes is beyond the scope of this report, but a key reason—in the case of programs aimed at changing participants’ behavior—is that behavior change is often hard to sustain over time. Readers who have tried to lose weight, quit smoking, begin exercising regularly, or keep a new year’s resolution likely understand that short-term success is much easier to achieve than sustained change, and relapse is common.

Another common cause of fade-out—in the case of programs aimed at increasing participants’ skills or credentials—is that the program may temporarily increase the skills/credentials of the program group relative to the control group, but the control group catches up over time. For example, an early literacy program in preschool classrooms may increase the program group’s ability to identify letters and words relative to the control group during the preschool year, but the control group children may then learn these skills in kindergarten and go on to read just as well as the program group children over time.

Whatever the reason, fade-out is a real phenomenon, and very common. For many programs, establishing a short-term effect is not yet evidence of a meaningful improvement in participants’ lives, and longer-term follow-up is an essential next step before declaring success.

References:

[i] For some types of programs and outcomes, short-term effects can be of great policy importance and fade-out need not be a major concern. Illustrative examples include (i) a reduction in neonatal mortality from a program that provides support groups for pregnant women and new mothers; (ii) reductions in rape on college campuses from a sexual assault resistance program for first-year female students; and (iii) reductions in unnecessary and costly rehospitalizations of patients, as a result of a hospital discharge and home follow-up program. In such cases, the outcome of key policy importance occurs in the near-term (e.g., within a year of random assignment), and the program may therefore be deemed a success even if there are no effects in future years.

In addition, some inexpensive social programs may still be worthwhile from a policy perspective if their effects fade over time but last long enough to justify the program’s low cost.

[ii] In the Cochrane reviews, the only RCTs measuring opioid use over a period of more than one year are a Swedish RCT of methadone maintenance with a sample of 35 addicts published in 1981, and an RCT of methadone maintenance in Hong Kong with a sample of 100 addicts published in 1979–both of which found sustained reductions in opioid use but are limited by small samples and (in the case of the Hong Kong RCT) very high sample attrition. The naltrexone RCT was published after completion of the Cochrane reviews, and so is not included in the reviews. The same is true of Hser et. al. 2016, a well-conducted RCT that randomized 1,080 opioid addicts to either buprenorphine treatment or methadone treatment (there was no non-medication control group). The study found that the methadone group had significantly lower opioid use than the buprenorphine group over a follow-up period that averaged 4.5 years. This study, like the naltrexone RCT, is a rare exception in a field where almost all RCTs are of short duration.

[iii] At the seven-year follow-up, the study found suggestive positive effects for the lowest-income students in the sample, including an increase in degree completion (5.5 percentage points, not statistically significant) and the cumulative number of semesters enrolled (0.9 semesters, statistically significant). These subgroup effects are best viewed as preliminary until corroborated in future studies because they could be “false positives” that occurred by chance due to the study’s estimation of effects on multiple outcomes and subgroups.

[iv] The per-student cost of Career Academies varies widely depending on the specific features of the school. An analysis of four Career Academies in California found that the high schools operating these Academies incurred total additional costs that ranged from approximately $3,800 to $7,600 per Academy student over the course of their three- or four-year Academy participation (in 2019 dollars). Source: Parsi, Plank, and Stern 2010.