Highlights:

- This report discusses new findings from a well-conducted randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Camden Coalition’s hotspotting program for patients with very high use of health care services (“superutilizers”). The program has been heralded in the national press as a flagship example of a promising superutilizer program.

- The RCT findings were disappointing: The program was found not to produce the hoped-for reductions in patients’ hospital utilization or costs.

- This RCT illustrates the hazards of asserting program effectiveness based on less rigorous study methods. Earlier press accounts that the program produced “almost certain” “revolutionary” savings were based on a common but flawed analysis—a comparison of participants’ health care utilization after the program versus before.

- Jeffrey Brenner, the physician who developed the Camden program, provides an inspiring example of moral courage in seeking the truth about the program’s impact through an RCT.

- The findings are a reminder that surprisingly few rigorously evaluated programs are found to produce meaningful improvements in people’s lives. They underscore the need to reform U.S. social spending to test many, many, many programs in order to identify the exceptional ones that really work.

Earlier this month, The New England Journal of Medicine published findings from an RCT of the Camden Coalition’s hotspotting program for patients with very high use of health care services (i.e., “superutilizers”).[1] The findings, which received national press coverage, were disappointing: The program was found not to produce the hoped-for reductions in patients’ hospital utilization or costs. Based on our review, we believe this was a well-conducted RCT[2] that offers important lessons to policy officials, researchers, and others seeking evidence-based solutions to the nation’s social problems. What follows are a summary of the study and thoughts on its implications.

The New England Journal article provides a concise description of the Camden, N.J., hotspotting program:

“Since being profiled in Atul Gawande’s seminal New Yorker article, ‘The Hot Spotters,’ the program … has been a flagship example of a promising superutilizer program. The Coalition’s Camden Core Model uses real-time data on hospital admissions to identify patients who are superutilizers, an approach referred to as ‘hotspotting.’ Focusing on patients with chronic conditions and complex needs … the program uses an intensive, face-to-face care model to engage patients and connect them with appropriate medical care, government benefits, and community services, with the aim of improving their health and reducing unnecessary health care utilization.

“The program has been heralded as a promising, data-driven, relationship-based, intensive care management program for superutilizers, and federal funding has expanded versions of the model for use in cities other than Camden, New Jersey.”

Here is our brief summary of the RCT and its key findings:

The study team randomly assigned a sample of 800 superutilizers who had been admitted to two major Camden, N.J., hospitals to either (i) a treatment group that received the hotspotting program, or (ii) a control group that received usual community services. The patients averaged 3.5 hospitalizations in the past year (including the one in which they entered the study). Treatment group members had a high level of program take-up and engagement with program services over the course of the study.

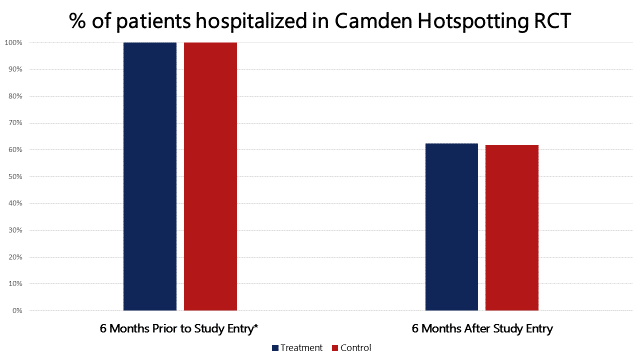

The study found no significant effect on the primary targeted outcome—the rate of rehospitalizations during the 180 days after patient discharge (62.3 percent of treatment group members were rehospitalized versus 61.7 percent of control group members). The study also found no significant effects on any of the pre-registered secondary outcomes (e.g., number of hospitalizations, hospital charges, mortality) or subgroups (e.g., patients with three or more hospitalizations in the prior year).

This RCT illustrates the hazards of asserting program effectiveness based on less rigorous study methods.

The 2011 New Yorker article that raised the national profile of the Camden program cited, as evidence of the program’s effectiveness, participants’ much lower rate of health care utilization after program participation versus before:

“The Camden Coalition has been able to measure its long-term effect on its first 36 superutilizers. They averaged 62 hospital and emergency room visits per month before joining the program and 37 visits after—a 40 percent reduction. Their hospital bills averaged $1.2 million per month before and just over half a million after—a 56 percent reduction. These results don’t take into account [the program’s] personnel costs … or the fact that some of the patients might have improved on their own…. The net savings are undoubtedly lower, but they remain, almost certainly, revolutionary.” [italics added]

This type of before and after, or “pre-post,” analysis—although very common in policy discussions—is not a credible method of assessing program impact. The reason is that, without reference to a control group of comparable individuals who do not receive the program, it cannot answer whether participants’ improvement over time would have occurred anyway in the program’s absence. In the case of hotspotting, individuals entering the program have exceptionally high health care utilization, and their utilization might be expected to move closer to the average over time even without a program—a phenomenon known as “regression to the mean.” That’s exactly what the RCT found:

As you can see, the hospitalization rate fell as sharply in the control group as it did in the treatment group over time; the RCT thus found that the program had no net effect on hospitalization rates. The New Yorker article’s conclusion that Camden hotspotting produced “almost certain” “revolutionary” health care savings was based on very weak evidence, and it turned out to be wrong.

Jeffrey Brenner, the family physician who developed the Camden program, provides an inspiring example of moral courage in seeking the truth about the program’s impact.

“We could have coasted on the publicity we were getting,” he told the New York Times. In addition to the 2011 New Yorker article and many other positive press stories, Brenner had received a MacArthur genius award for his work on the Camden program. Yet, as Amy Finkelstein—the lead researcher on the Camden RCT—told Reuters Health, Brenner and his organization “completely embraced” the study. “Dr. Brenner said, ‘We think what we’re doing is having an impact, but we won’t know until we do a randomized evaluation. If it doesn’t work, we need to figure out why and try something else.’”

As to the study’s findings, Brenner told NPR, “It’s my life’s work. So, of course, you’re upset and sad.” But he and the Camden Coalition underscore that it’s important to keep figuring out what is going to work and not to give up. (In the Times article, Brenner discusses possible reasons for the program’s lack of impact and his latest experiment in providing housing to high-cost patients.)

The study findings are an important reminder of how challenging it is to develop programs that are truly effective, as demonstrated in a high-quality RCT.

We know from the history of rigorous evaluations that surprisingly few programs and strategies produce the hoped-for improvements in participants’ lives—and this is true even of programs such as Camden hotspotting that are well implemented and have strong logical plausibility. In earlier Straight Talk reports [a,b], we have described this as the central challenge—the “800-pound gorilla”—that stymies progress in solving our nation’s social problems.

The good news is that success is possible. Among programs aimed at reducing cost and improving care for high-utilizing patient populations, well-conducted RCTs have identified a few programs that produce sizable positive effects (such as the Transitional Care Model) amid others that do not (e.g., see the federal Medicare Health Support and Medicare Coordinated Care RCTs).

Finally, the results underscore why U.S. social spending must strongly incentivize this type of evidence-building if we hope to make progress on major social problems.

The history of rigorous evaluation makes clear that we need to test many, many, many approaches if we hope to identify a sizable number with meaningful positive effects, given the odds against success for any particular program approach. But, compared to a field like medicine, RCTs are still fairly uncommon in social policy, as their occurrence depends on exceptional individuals like Brenner stepping forward—often against self-interest—to put their program to an ultimate test. If our plan for solving the nation’s social problems is to rely on just these few pioneers, progress on poverty, health care costs, educational failure, drug abuse, and other problems will be very slow indeed.

Alternatively, we can take a fundamentally different tack, akin to that used in medicine: Reform U.S. social spending programs to incentivize—or, where appropriate, require—funding recipients to engage in rigorous evaluations to determine the true impact of their activities. Doing so would be the 21st century’s answer to President Franklin Roosevelt’s call for “bold, persistent experimentation” in government, and we have previously outlined how such an approach might work. Jeffrey Brenner’s program may not have achieved the hoped-for effects, but if his example can help stimulate this type of policy reform, it would be a valuable legacy indeed.

Response provided by the lead study author:

We invited the lead study author, Amy Finkelstein, to provide written comments on our report. She said that she was glad to see the report, and had no reason to provide comments.

References:

[1] Arnold Ventures provided funding support to J-PAL North America at MIT to help launch the U.S. Healthcare Delivery Initiative under which this study was carried out.

[2] For example, the study had a sizable sample of patients, successful random assignment (as evidenced by highly similar treatment and control groups), negligible sample attrition, and valid analyses that were publicly pre-registered.