Highlights:

- We discuss newly-published long-term findings from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the federal Job Corps program, the nation’s largest residential career training program for at-risk youth.

- We believe this was a well-conducted RCT that, unfortunately, selectively reported its main findings in the study abstract. The abstract is very important; for busy readers who do not purchase and review the full 30-page article, it may be all they ever read on the study results.

- The abstract highlights positive results for a subgroup of youth to claim “this study is the first to establish that a national program for disconnected youth can produce long‐term labor market gains.”

- The abstract does not mention the central study finding of no statistically significant effects on any outcome for the full sample of Job Corps participants, nor the adverse findings for another key subgroup of youth. It also portrays the positive subgroup findings as reliable when they could well be “false positives” resulting from the study’s measurement of numerous effects.

- Such selective reporting – a pervasive problem in the evaluation literature – could easily lead policy officials to believe Job Corps has demonstrated long-term positive effects when that is not the case, and undercut efforts to reform Job Corps so that it does produce meaningful sustained effects.

- A response from the study author, and our rejoinder, follow the main report.

In this report we discuss newly-published findings in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (JPAM) on the long-term effects of the federal Job Corps program. Job Corps, established in 1964, is the nation’s largest residential career training program for at-risk young people age 16 to 24. The U.S. Department of Labor sponsored a nationwide RCT of Job Corps in the 1990s, with a sample of over 15,000 young people. The new JPAM article reports findings on the long-term effects of Job Corps, measured approximately 20 years after study enrollment.

Our concern, detailed below, is that the study abstract – which is designed to summarize the central results – reports positive findings while omitting other, disappointing findings that cast doubt on the program’s long-term effectiveness. Such selective reporting – a pervasive problem in the evaluation literature – could easily lead policy officials to believe that Job Corps has rigorously-demonstrated long-term positive effects when that is not the case.

The study abstract portrays the findings as positive, stating that “this study is the first to establish that a national program for disconnected youth can produce long‐term labor market gains.” We focus on the study abstract because its purpose is to summarize the main findings and, for many busy readers who do not purchase and review the full 30-page paper, it may be all they ever read on the study results. Here is the full abstract:

Job Corps is the nation’s largest and most comprehensive career technical training and education program for at‐risk youth ages 16 to 24. Using the sample from a large‐scale experiment of the program from the mid‐1990s, this article uses tax data through 2015 (20 years later) to examine long‐term labor market impacts. The study finds some long‐term beneficial effects for the older students, with employment gains of 4 percentage points, 40 percent reductions in disability benefit receipt, and 10 percent increases in tax filing rates in 2015. For these students, program benefits exceeded program costs from the social perspective. This study is the first to establish that a national program for disconnected youth can produce long‐term labor market gains, and can be a positive investment made for society. The results suggest that intensive, comprehensive services that focus on developing both cognitive and noncognitive skills are important for improving labor market prospects for this population.

The selective reporting problem: The abstract reports only positive results and omits other primary study findings that cast doubt on the program’s long-term effectiveness.

1. As background, the study’s primary outcomes in this long-term follow-up are participants’ employment and earnings over 2013-2015.

A study’s “primary” outcomes are the outcomes that test the study’s central hypotheses and are the main basis for determining the program’s effectiveness. In this study of Job Corps’ long-term effects, the author pre-specified employment and earnings, measured in the last three years of the follow-up period (2013, 2014, and 2015), as the primary outcomes. The author pre-specified that these outcomes would be measured for the full study sample and for three subgroups based on sample members’ age at study enrollment: (i) age 16-17; (ii) age 18-19; and (iii) age 20-24.[1]

2. The abstract highlights positive employment effects for the oldest subgroup (age 20-24), but nowhere mentions the lack of employment and earnings effects for the full sample.

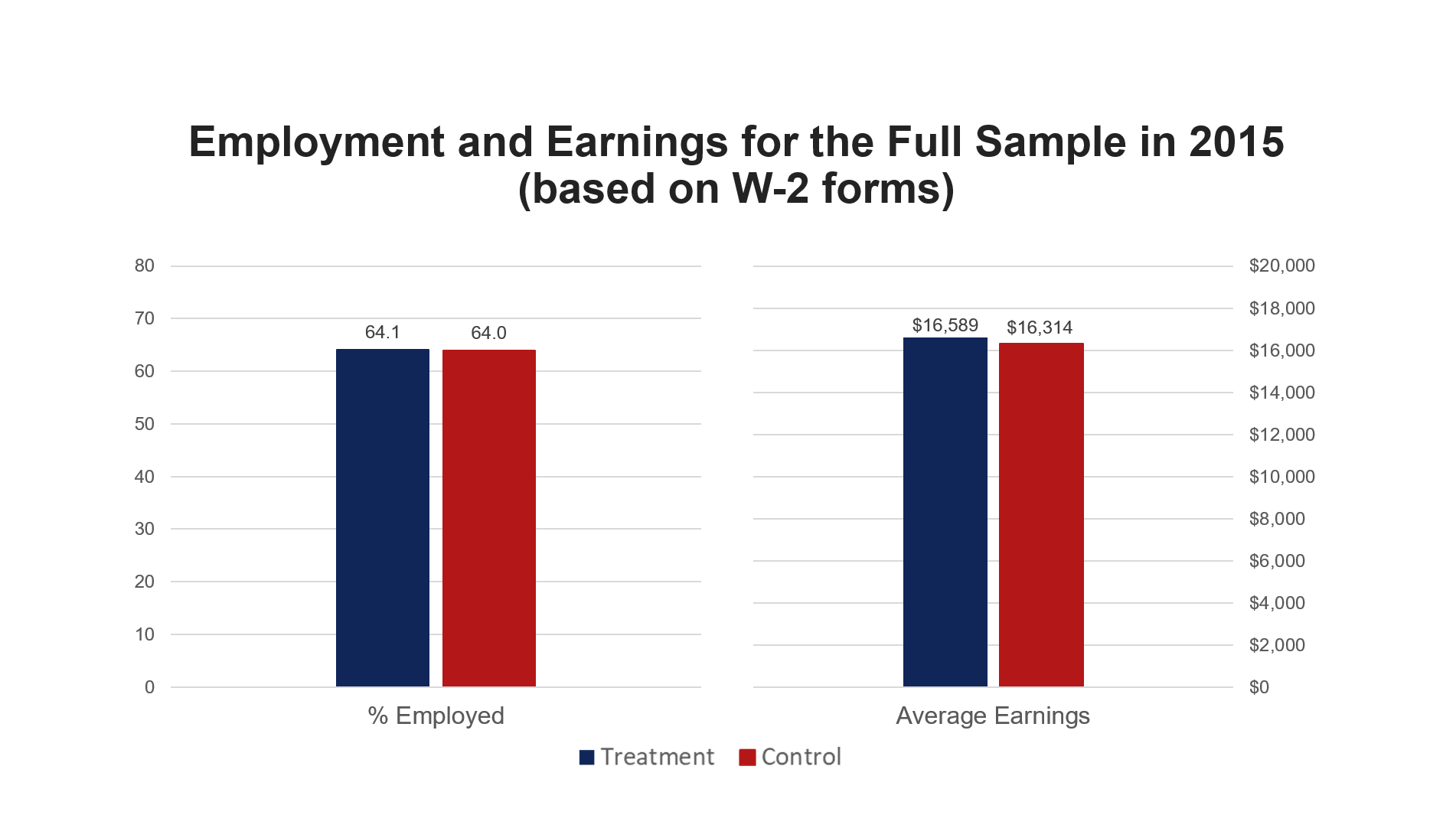

The study found no statistically significant effects on employment or earnings for the full sample in any of the three follow-up years. Here is a graph of the outcomes for the full sample in the final follow-up year, showing that the treatment group and control group outcomes were almost identical: 3. The abstract also does not mention that the study found statistically significant adverse effects on employment for the age 18-19 subgroup in two of the three follow-up years.

3. The abstract also does not mention that the study found statistically significant adverse effects on employment for the age 18-19 subgroup in two of the three follow-up years.

While the abstract highlights positive effects on the age 20-24 subgroup – a 4 percentage point increase in employment in 2013, 2014, and 2015 – it does not mention the adverse employment effects for the age 18-19 subgroup. For this subgroup, the treatment group’s employment rate was 5 percentage points lower than that of the control group in 2013 and 2014.[2]

4. The positive employment effect for the age 20-24 subgroup, highlighted in the abstract, is not a reliable finding under established scientific standards.

The fact that the study measured eight effects on the primary outcomes (employment and earnings, each estimated for the full sample and three subgroups) means that the study is at substantial risk of generating “false-positive” results – that is, statistically significant findings that appear by chance due to the study’s measurement of multiple effects.[3] In such cases, respected scientific bodies such as the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) require a “multiplicity adjustment” to the statistical significance tests to account for the higher chance of false positives (see IES guidance, pp. 6-7, and FDA draft guidance, pp. 9-10).

Prior to the application of a multiplicity adjustment, the study’s finding of positive employment effects for the age 20-24 subgroup approached, but did not reach, statistical significance at conventional levels (p=0.08 in each of the three follow-up years).[4] When we apply a multiplicity adjustment, this finding no longer approaches statistical significance and therefore is considered preliminary and unreliable under accepted standards. (The adverse finding found for the age 18-19 subgroup also loses its statistical significance once a multiplicity adjustment is applied.)[5]

5. The abstract also cites beneficial effects on disability benefit receipt and tax filing in the age 20-24 subgroup, but these are not primary outcomes and the findings are thus not reliable.

In the absence of credible effects on the primary outcomes, the effects on non-primary outcomes such as disability benefit receipt and tax filing are not considered reliable under accepted scientific standards, for reasons described in the IES and FDA guidance documents (see IES pp. 4-7, FDA pp. 9-21). But an intuitive explanation in this case is that the Job Corps study measured over 40 effects on non-primary outcomes as part of the long-term follow-up, and found only two that were statistically significant at conventional levels (i.e., disability benefit receipt and tax filing). These could easily be false positives given the tendency of statistical significance tests to produce some false findings when numerous effects are measured, as discussed above.

This inaccurate portrayal of the study findings could easily lead policy officials to believe that Job Corps has demonstrated long-term positive effects when that is not the case. A balanced summary of the study’s findings would state that the estimated long-term effects on employment and earnings for the full sample are near zero, and that the positive findings for the age 20-24 subgroup and the adverse findings for the age 18-19 subgroup are not statistically significant and could well be due to chance.

This long-term evaluation of Job Corps is an excellent study with findings of great policy importance. But the abstract’s inaccurate portrayal of the study results could undercut efforts to reform Job Corps so that it actually does produce meaningful improvements in participants’ long-term economic outcomes. Consistent with Nobel laureate Richard Feynman’s entreaty to graduating Caltech students in 1974, we believe the study author and publishing journal have a responsibility to policy officials, future Job Corps participants, and society to present the findings in a balanced and neutral manner.

Response provided by Peter Schochet, the study author

The commentary raises important issues about how results from impact evaluations in the social policy area should be interpreted. While the commentary questions the scientific merit of the evaluation findings presented in the article abstract only, the criticism of “fishing for findings” seems to extend to the main text also. My comments focus on this broader criticism.

I am a firm believer in pre-specification of primary hypotheses for RCTs to help structure analyses and guide interpretation and have published on the importance of this practice (Schochet 2009). However, when conducting RCTs of social policy interventions, pre-specification strategies often need to be tailored to the policy context. The commentators apply a strict FDA standard for medical trials to review the findings. However, they ignore the actual pre-specification strategy adopted for the study, fail to address why this strategy is problematic, and instead choose to cite the study as an exemplar of poor research practice.

The evaluation’s pre-specification strategy was designed to balance the following questions, recognizing policymakers’ need for information on Job Corps:

- What is the desired balance between Type 1 errors (the chances of finding spurious findings) and Type 2 errors (the chances of missing true findings)? Should multiple comparisons corrections be applied to test all primary hypotheses within and across outcome domains?

- Should primary analysis results be the only guide for drawing study conclusions? What is the role of other analysis findings, such as those for secondary and mediating outcomes, subgroups, and process studies, especially if they support primary analysis results? What role should benefit-cost analysis results play?

As Job Corps is well-established, policymakers need information not only on its overall effectiveness, but also on how it can be improved. Hence, the adopted pre-specification strategy used a broader set of principles than the “thumbs-up/thumbs-down” FDA approach (see article). Using this strategy, a fair reading of the evidence suggests that Job Corps was beneficial for the older students (a pre-specified primary subgroup): benefits exceeded costs; primary impacts were marginally significant in some years; employment and earnings were higher for the treatment group in all years but one; and secondary and process analyses provide supporting evidence.

The abstract appropriately tempers the findings by stating there is “some,” not “definitive,” evidence of effects for the older students. Further, the main text presents all findings, leading with the primary hypotheses, contrary to the levied criticism that the article cherry-picks findings. The lack of impacts for the full sample is the lead point in all relevant sections, and is implied in the abstract, although this point could be made explicit (and I will request this).

As discussed in the conclusions, study results over 20 years suggest the Job Corps model shows promise (unlike many other training programs with less intensive models), though improvements are needed. Do the commentators disagree? While pre-specification is critical for scientific rigor, the broader question is whether a uniform FDA standard (that applies multiplicity corrections to all primary analyses and ignores corroborating evidence) is always appropriate for social policy evaluations.

Rejoinder by Arnold Ventures’ Evidence-Based Policy team

We appreciate the study author’s thoughtful reply and, consistent with his comments, would note that the study exemplifies good research practice in several respects: (i) it is a large, well-conducted RCT; (ii) the author pre-specified the outcomes and subgroups to be examined in this long-term follow-up; and (iii) the main text presents findings on all of these outcomes and subgroups.

Our concern lies in the selective reporting of the study’s main findings in the abstract. The abstract is an extremely important element of the study. For many policy officials and other readers, the abstract may be their only exposure to the study findings, and they will likely trust that it provides a balanced, impartial overview of the study’s headline results.

In this case, the trust is misplaced. As noted in our main report, the abstract:

- Does not mention that the study found no long-term effects on any outcome for the full sample of Job Corps participants;

- Mentions the positive effects for the age 20-24 subgroup, but not the adverse effects for the (somewhat larger) age 18-19 subgroup; and

- Portrays the age 20-24 subgroup findings as reliable (e.g., stating “this study is the first to establish that a national program for disconnected youth can produce long‐term labor market gains”) when that is not the case under established scientific standards, since these findings could well be false positives resulting from the study’s measurement of numerous effects.

Regarding item (iii) on the reliability of the subgroup findings, the author’s response states that we are applying an FDA standard to adjust for the possibility that the subgroup findings could be false positives, which is not always appropriate for social policy evaluations. We note, however, that respected scientific bodies in social policy such as the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) also require such an adjustment (see IES pp. 4-7, and What Works Clearinghouse, pp. F-3 to F-4).

To understand why this study’s subgroup findings are not considered reliable under FDA or IES standards, consider that the study measured and reported a total of 68 long-term effects of Job Corps on various outcomes and subgroups, and found 2 positive effects and 2 adverse effects that were statistically significant at conventional levels (p<0.05). This is roughly the pattern that one would expect if the program produced no true effects on any outcome or subgroup, since approximately 1 out of 20 statistical significance tests can be expected to produce a false finding.[6]

Finally, we appreciate the author’s plan to request a revision to the study abstract to mention the lack of effects for the full sample. We would encourage him to also mention the other items noted above in a revised abstract so as to provide a fully balanced presentation of the study’s key results.

References:

[1] The author pre-specified the primary outcomes and subgroups in a study design report to the Department of Labor for this long-term follow-up. The Department did not publish the design report.

[2] In 2015, the treatment group’s employment rate in the age 18-19 subgroup was 2 percentage points lower than that of the control group, but this difference was not statistically significant.

[3] For each effect that a study measures, there is roughly a 1 in 20 chance that the test for statistical significance at the 5 percent level will produce a false-positive result when the program’s true effect is zero. So a study like this that examines a program’s effect on multiple outcomes and subgroups is at substantial risk of generating such false positives.

[4] The conventional standard for statistical significance is p<0.05.

[5] We applied the Benjamini-Hochberg multiplicity adjustment to the eight primary effects measured in 2013, to the eight measured in 2014, and to the eight measured in 2015. When we did so, no effect in any of the three years reached statistical significance (p<0.05) or approached significance (p<0.10).

[6] Including effects that are statistically significant (p<0.05) or near-significant (p<0.10), the study found a total of 6 positive effects and 3 adverse effects – a pattern that is also roughly what one would expect if the program produced no true effects on any outcome or subgroup (since approximately 1 out of 10 significance tests can be expected to produce a false finding under a “near significant” standard).