Highlights:

- In our last report, we noted that short-term effects of social programs too often fade over time.

- In this report, we highlight an exceptional case: Newly-reported findings from a well-conducted randomized controlled trial (RCT) of Project QUEST, a workforce training program for low-income individuals. The study found that QUEST produced a 20 percent gain ($5,490) in participant earnings in the ninth year after program entry, compared to the control group.

- QUEST is currently the only U.S. workforce training program shown in a well-conducted RCT to produce such sizable, enduring effects. While highly promising, we believe the findings need to be replicated in a second RCT to have confidence that QUEST would produce similar effects if implemented elsewhere.

- QUEST shares features with other training programs that have highly-promising RCT evidence. Such features include: (i) training focused on strong sectors of the local economy where well-paying jobs are available; (ii) partnership with local employers; (iii) required full-time enrollment in the program.

- This is the type of evidence our country needs to address one of our most pressing national problems: Four decades of income stagnation for low- and moderate-income Americans.

- A thoughtful comment from the study authors follows the main report.

In our last Straight Talk report, we noted that short-term program effects can fade over time, and that excitement over initial evaluation findings too often ends in disappointment when longer-term results come in. In today’s report, we’re very pleased to share an exceptional case: Newly-reported nine-year findings from the randomized controlled trial (RCT) of Project QUEST, a workforce training program for low-income individuals. The full study report is Economic Mobility Corporation 2019; the following is our brief overview (disclosure: Arnold Ventures funded the study’s long-term follow-up).

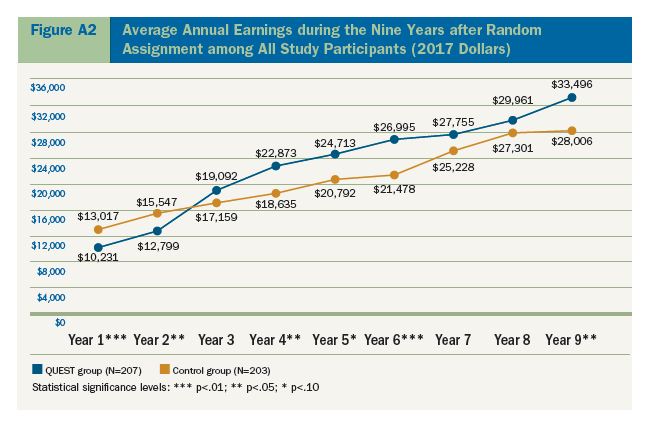

This is a well-conducted RCT of Project QUEST in San Antonio, Texas. QUEST provides comprehensive support and resources to help low-income individuals enroll full-time in occupational training programs at local community colleges, complete the training, pass certification exams, and enter well-paying careers in high-growth sectors of the local economy. Between 2006 and 2008, the researchers randomly assigned 410 low-income individuals who were interested in nursing, medical records coding, or other health-related training to (i) a program group that received QUEST services focused on healthcare occupations, or (ii) a control group that did not receive these services. The program’s cost was approximately $11,700 per person in 2017 dollars. The study measured earnings outcomes for all sample members over a nine-year period using Texas unemployment insurance records. Here are the results:

Source: Economic Mobility Corporation 2019. Our one-page review of the study is linked here.

As you can see, the program’s effects on annual earnings—depicted as the gap between the blue line (program group earnings) and orange line (control group earnings)—are both sizable and enduring. Specifically:

- The effect on the study’s primary, pre-specified outcome for the long-term follow-up—earnings in the ninth year after random assignment—was a statistically-significant increase of 20 percent, or $5,490 ($33,496 for the program group versus $28,006 for the control group, in 2017 dollars).

- Over the full nine years, program group members earned an average of $20,753 more than control group members.[1]

We offer three brief observations on these findings and their policy implications, as follows.

First, QUEST is currently the only U.S. workforce training program that has been shown in a well-conducted RCT to produce such long-term, sizable effects on the economic well-being of program participants. This is a remarkable achievement, with an important caveat: We believe the finding needs to be replicated in a second RCT to have confidence that QUEST would produce similar effects if faithfully implemented in other jurisdictions. Positive findings from a single, high-quality RCT such as this sometimes replicate successfully (e.g., [a],[b],[c]), but sometimes do not (e.g., [d],[e]). The only way to know for sure whether the QUEST findings replicate would be to do another study in a different site.[2] If the early results of the new study—for example, in years three and four—are similar to those found in the first QUEST RCT, one could tentatively conclude that the program’s sizable effects are reproducible and generalize to other settings, warranting further expansion of QUEST while the study continues to go forward to hopefully confirm that the effects endure.

Second, QUEST is an example of a particularly promising type of workforce training called “sectoral” training. Sectoral training programs (i) focus on high-growth sectors of the local economy where well-paying jobs are available (in the QUEST RCT, the healthcare sector); and (ii) work in close partnership with local employers to develop the training content and provide work opportunities to program participants. An additional core feature of QUEST is that it requires participants to enroll in training full-time, so as to complete the program in an efficient manner. In earlier Straight Talk reports, we discussed two other sectoral programs with these core features—Per Scholas and Year Up—that have been found in well-conducted RCTs to produce sizable earnings gains over at least a three-year period, and there are other positive examples, albeit with more preliminary evidence. Not all sectoral training programs have been found to produce significant effects when rigorously evaluated, but the promising overall pattern suggests that further investment in this approach—for example, to develop and test new sectoral programs to serve other types of workers—is warranted.

Third, this is the type of evidence that our country needs to address one of our most pressing national problems: Four decades of income stagnation for low- and moderate-income Americans. It is a problem that has persisted despite numerous policy initiatives that were supposed to help, such as (i) major tax cuts in the 1980s and 2000s designed to spur economic growth and productivity and thereby raise worker wages; and (ii) large public investments in job training and education programs for low- and moderate-income populations, aimed at imparting the skills they need to succeed economically (but which, when rigorously evaluated, are too often found not to produce the hoped-for effects). We have previously described the existing approach as “government by guesswork,” with little to show in the way of meaningful progress since the late 1970s.

Our nation can spend the next 40 years guessing at solutions to the income stagnation problem, with no reason to believe we’ll see different results. Or, we can take a fundamentally different approach to problem-solving, akin to that used in medicine: Recognize that most programs and strategies don’t produce the hoped-for effects but some exceptional programs do, and reinvent social spending so as to build and deploy proven-effective programs on a major, government-wide scale. It would be the 21st century’s answer to President Franklin Roosevelt’s call for “bold, persistent experimentation” in government, and we have previously outlined how the approach might work. As QUEST and other exceptional RCT findings illustrate, it offers a path to progress in improving the lives of low- and moderate-income Americans that spending as usual does not.

Response provided by Mark Elliott and Anne Roder, the study authors

We appreciate the Straight Talk authors recognizing Project QUEST’s achievement of demonstrating the largest sustained earnings gains ever found in a rigorous evaluation of a workforce development program. As the authors note, while QUEST is exceptional, it does not stand alone. Indeed, QUEST was part of an initiative we launched fifteen years ago at Public/Private Ventures that entailed randomized controlled trial evaluations of three other sectoral training organizations: Per Scholas, JVS Boston, and Wisconsin Regional Training Partnership. At each of these organizations, participants realized statistically significant earnings gains in the years following enrollment. As such, they stand as an emphatic counterpoint to the conventional wisdom that investing in the skills of low-income people is not worthwhile.

Nobel laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz wrote recently in the New York Times, “The U.S. has the highest level of inequality among the advanced countries and one of the lowest levels of opportunity. But things don’t have to be that way.” We agree. Even in today’s hyper-partisan policy environment, surely people on the left and on the right can acknowledge that it’s a good idea to invest in programs that enable low-income Americans to advance.

Despite their success in demonstrating earnings impacts, these four organizations struggle to maintain funding for their programs. Entrepreneurial leaders have enabled each to survive, but it hasn’t been easy. In fact, QUEST nearly shuttered its doors in 2010 due to a funding shortfall.

We concur with the Straight Talk authors that the federal government should abandon its “government by guesswork” strategy and make an explicit commitment to invest in proven programs. We believe that foundations and wealthy individuals should do the same, and we recommend the creation of a five-year, $500 million investment fund, with foundation commitments to be matched by government support, that will offer substantial capital to any nonprofit organization that has demonstrated large earnings impacts in a rigorous evaluation. By offering grants to replicate and expand proven strategies, the fund would simultaneously reward organizations that have taken the risk of undergoing a randomized controlled trial evaluation, encourage other organizations to adopt similar strategies, and enable many thousands of people to achieve upward mobility.

References:

[1] As shown in the graph, the program group’s earnings were lower than the control group’s earnings in the first two years of the study, as program group members reduced their work hours or stopped working to participate in the program. The program group’s earnings exceeded the control group’s earnings in year three (upon program completion) and thereafter.

[2] An RCT of a very similar model—Valley Initiative for Development and Advancement (VIDA)—is currently underway and has reported encouraging initial findings.