Arnold Ventures Policy Proposal Would Capitalize on Results to Increase U.S. Economic Mobility

Highlights:

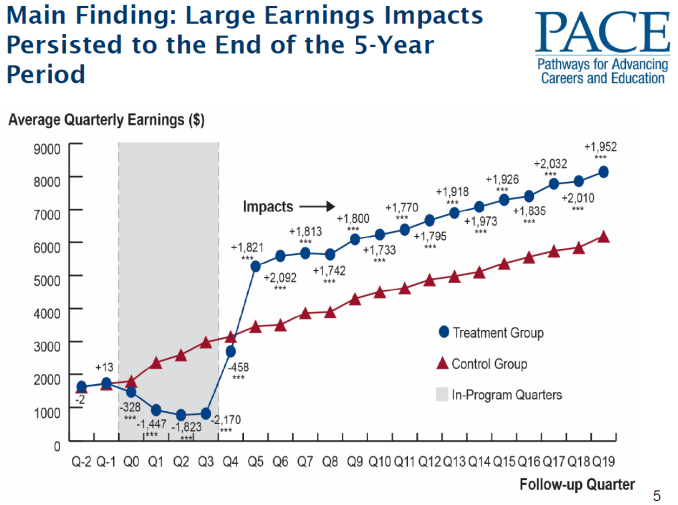

- New findings from a national randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Year Up workforce training program show earnings gains of 30-40% ($7,000-$8,000) per year, sustained over five years, for low-income, mainly minority young adults.

- These earnings gains are among the largest ever found in a high-quality RCT in the field of workforce development – an area where such RCTs too often find disappointing effects.

- The study found sizable earnings effects in each of the eight participating U.S. cities, establishing that the findings generalize across diverse settings.

- Year Up joins a small but growing number of workforce development programs with high-quality RCT evidence of sizable, sustained earning effects.

- Policy officials should expand these programs; if done effectively and on a large scale, they could move the needle on economic mobility and racial equity for millions of low-income Americans.

- We offer a policy proposal – the Funding Match for Evidence initiative – to accomplish this by integrating these proven programs into existing federal, state, and local spending streams.

- A thoughtful comment from the lead study author follows the main report.

Two years ago, we wrote about highly-promising initial findings for Year Up – a workforce training program for low-income young adults – in a large RCT sponsored by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Administration for Children and Families. The key study limitation, we noted at the time, was that it only measured outcomes over a relatively short period, so it was not yet known whether the large effects found on participants’ earnings would endure or (as too often occurs) dissipate over time.

The study’s longer-term findings were recently reported at an HHS conference [a,b], and we’re pleased to share that they are extremely impressive – indeed, the earnings effects are among the largest ever found in a high-quality RCT in the field of workforce development.[1] In this Straight Talk report, we discuss the new findings, and propose a concrete next step that federal officials can take – based on these and other recent impressive RCT findings – to move the needle on economic mobility for low and moderate income individuals on a national scale.

The new Year Up RCT findings: Earnings gains of 30-40% ($7,000-$8,000) per year, sustained over five years, for low-income, mainly minority young adults

Year Up is a full-time, year-long workforce training program for low-income young adults that focuses on economic sectors with jobs in high demand – namely, information technology and financial services.[2] The HHS RCT is evaluating the program in eight U.S. cities with a sample of 2,544 low-income individuals, 85% of whom are Black or Hispanic. The new findings, covering the five-year period after random assignment, show that the program increased average earnings by 30-40% ($7,000-$8,000) per year with no sign of diminishing over time:

We offer four brief observations on these findings, as follows.

1. This is definitive evidence of Year Up’s effectiveness when delivered on a large scale under typical implementation conditions across eight U.S. cities. In addition to the large overall effect found in a well-conducted RCT, the effects in each of the eight cities were sizable and statistically significant, providing evidence for the robustness and generalizability of the findings across diverse settings. This means that, if Year Up were to expand to other cities and be implemented faithfully in a population similar to the RCT sample, those cities can be confident – even without a new evaluation – that the program will produce sizable earning gains for program participants. The “similar population” condition is important. Year Up carefully screens applicants and enrolls those identified as being motivated to succeed and interested in career advancement; thus, the effects may not apply to young adults who fall outside these criteria.

2. Year Up joins a small but growing number of workforce development programs that have demonstrated sizable, sustained earnings gains in high-quality RCTs, such as Per Scholas, QUEST, Nevada REA, and Career Academies. Three of these programs – Year Up, Per Scholas, and QUEST – share common features and are sometimes referred to as “sectoral” job training programs, as we have described in a previous Straight Talk report.

3. Such highly-effective programs are the exception; surprisingly few rigorously-evaluated social interventions – in workforce development and other areas – are found to produce the hoped-for effects. In earlier Straight Talk reports, we have described the scarcity of truly effective strategies as the central challenge – the “800 pound gorilla” – that stymies progress in solving our nation’s social problems.[c,d,e,f]. It is the reason we believe policy officials should take exceptional findings such as the Year Up results very seriously and act on them, as discussed below.

4. Year Up’s cost to taxpayers – were the program to be expanded with government funding – is reasonable (about $12,000 per participant). The program’s total cost is approximately $28,000 per participant, but most of that cost (about $16,000) is borne by employers who provide internships to Year Up participants as part of the program and pay Year Up for each intern. Thus, the likely cost of program expansion to the taxpayer is about $12,000 per participant, as one could reasonably expect substantial co-funding by local employers.[3] As a point of reference, the cost to the taxpayer of Job Corps – a major federal job training program for youth – is over $25,000 per participant, and Job Corps produces much smaller earnings effects (based on a high-quality RCT) that quickly fade over time.[g,h,i,j]

The Year Up study authors conducted a cost-benefit analysis of Year Up, based on the RCT findings, and report positive results. However, details of that analysis are not yet available so we have not reviewed it.

Proposed next step for policy officials to put proven-effective programs like Year Up into widespread use: The federal “Funding Match for Evidence” initiative (linked here, two pages)

The proposed Funding Match for Evidence initiative would provide an opportunity for states and localities to qualify for additional federal match funding if they dedicate some of their existing funds from federal, state, and other sources to the expansion of programs like Year Up that meet the highest evidence standards. As an illustrative example, the federal government currently provides approximately $3 billion each year to states for the training and employment of youth, adult, and dislocated workers under Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, or WIOA. Per the Funding Match proposal, states that opt to use some of their WIOA funds to expand Year Up or other proven-effective programs (with close adherence to the key program elements) would receive additional match funds for that expansion. The goal is to integrate these proven programs into existing federal, state, and local spending streams, so that they reach much larger populations of Americans who can benefit.

Conclusion: As the Year Up RCT convincingly demonstrates, evidence-based policy is delivering on its promise to build a body of proven programs that can move needle on economic mobility. It is time to act on the findings.

Response provided by David Fein, the lead study author

We appreciate the opportunity to comment on this review of the new findings on Year Up. Our comment builds on two themes in the review—that Year Up’s costs are reasonable and that it deserves high priority in initiatives to scale effective programs.

On costs, we agree that $12,000 per participant is a reasonable ask of taxpayers for a program that can raise the remaining $16,000 of its costs from private companies and return $1.66 to society for every dollar spent overall. Thanks to Year Up, we now know that substantial investments in these young adults can create lasting opportunities for them that also are worthwhile to society at large. It may be possible to match Year Up’s results with somewhat less intensive approaches, and it is surely worth testing lower-cost versions of its model. But the current findings also should leave us wary of the notion that quick, inexpensive solutions can solve deep-seated social problems.

On financing mechanisms, our estimated $1.66 return embodies the assumption that firms receive financial benefits equal to half of what they spend on interns—benefits such as interns’ work contributions and more cost-effective pipelines to entry-level talent. But the societal benefit was still positive when we assumed zero return to firms (an unlikely outcome). Of course, earnings impacts might diminish were taxpayers to foot the entire bill (employers’ incentives to nurture and hire interns might diminish if they had no “skin in the game”) but the simulation does suggest room for increasing the public share of the costs.

On initiatives to match and scale effective programs, the approach sketched in Arnold Venture’s “Funding Match for Evidence” proposal seems promising. Going forward, we would hope to see a clearer formulation of principles and mechanisms for maintaining fidelity to program design and implementation in such initiatives.

Our first Year Up report documented the many promising practices woven into this program and identified administrative capacities that helped to achieve a level of implementation not typically seen in workforce training programs. Organizationally, Year Up is remarkable for fusing a hard-headed, entrepreneurial ethos—and an ability to connect and engage major national firms at the highest levels—with the caring and devotion to young adults often found in social service agencies.

Especially rare is Year Up’s ability to arrange thousands of internships a year with Fortune 500 companies and generate revenue by providing firms a pipeline to well-screened, well-trained new hires. As noted above, this financing mechanism ensures that employers have skin in the game and thus a stake in nurturing and hiring program interns. Replicating this capacity will not be easy, but it is probably critical to scaling up Year Up’s impacts. Two good starting points would be to adopt Year Up’s excellent performance measurement system for monitoring program outcomes and give its leaders a major role in designing and overseeing programs aimed at repeating their success.

In sum, from inception “funding match for evidence”–style initiatives must embody clear and strong provisions for ensuring that grantees implement authentic versions of effective programs like Year Up.

References:

[1] HHS plans to release the full study report on the five-year findings in early 2021. Even though we have only seen the summary five-year results, we are confident they are valid based our careful review of the earlier study report and the fact that the new results are a straightforward update of the earlier findings based on administrative earnings data (HHS’s National Directory of New Hires).

[2] “Year Up” is also the name of the organization that implements the Year Up program.

[3] We are co-funding, with the Institute of Education Sciences, an RCT of a lower-cost version of Year Up delivered on college campuses – the “Professional Training Corps” – to see if similar earnings effects can be achieved at reduced cost.